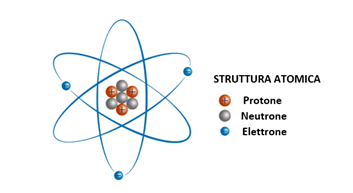

An ionic bond is an electrostatic interaction between a positively charged ion (cation) and a negatively charged ion (anion).

This bond occurs when the difference in electronegativity between the species is greater than 1.9.

The less electronegative species donates one or more electrons to the more electronegative species. The species that donates the electrons becomes a cation, while the species that receives the electrons becomes an anion..

IONIC BONDING IN SODIUM CHLORIDE NaCl

A common example of an ionic bond can be found in sodium chloride, the salt we use in our daily cooking.

The significant difference in electronegativity allows sodium (Na) to donate an electron to chlorine (Cl). This electron transfer is further favored by the electronic configurations of the two elements involved in the bond.

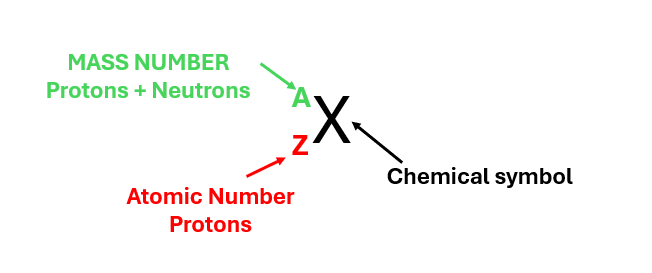

By donating one electron, the sodium atom becomes a Na⁺ ion and acquires the electronic configuration of neon, the noble gas that precedes it in the periodic table.

Na = 1s22s22p63s1 → Na+ = 1s22s22p6

By gaining one electron, the chlorine atom becomes a Cl⁻ ion and acquires the electronic configuration of argon, the noble gas that follows it in the periodic table.

Cl = 1s22s22p63s23p5 → Cl– = 1s22s22p63s23p6

The full octet in the electronic configurations of noble gases gives these elements a high degree of stability.

These ions arrange themselves into specific structures called crystal lattices, in order to maximize the attractive forces between oppositely charged ions and minimize the repulsive forces between like-charged ions.

IONIC BONDING IN CALCIUM CHLORIDE CaCl2

Another example of an ionic bond is found in calcium chloride, which is used in solutions such as antifreeze.

The significant difference in electronegativity allows calcium (Ca) to donate two electrons, one to each of two chlorine (Cl) atoms. This results in the formation of one Ca²⁺ ion for every two Cl⁻ ions formed.

This electron transfer is further favored by the electronic configurations of the two elements involved in the bond.

By donating two valence electrons, the calcium atom becomes a Ca²⁺ ion, acquiring the electronic configuration of the noble gas that precedes it..

Ca = 1s22s22p63s23p64s2 → Ca2+= 1s22s22p63s23p6

By gaining one electron, each chlorine atom becomes a Cl⁻ ion, acquiring the electronic configuration of the noble gas that follows it (Ar).

Cl = 1s22s22p63s23p5 → Cl– = 1s22s22p63s23p6

The full octet in the electronic configurations of noble gases gives these elements a high degree of stability.

These ions arrange themselves into specific structures called crystal lattices, in order to maximize the attractive forces between oppositely charged ions and minimize the repulsive forces between like-charged ions.

KEY CONCEPTS:

- An ionic bond involves the transfer of one or more electrons between different chemical species.

- The less electronegative species donate one or more electrons to the more electronegative species.

- An ionic bond is formed when the electronegativity difference is greater than 1.9.

- The oppositely charged ions arrange themselves in crystal lattices.